Cultural Roots

When Western listeners think of Indian classical music, many first recall the sitar — popularized in the West by Ravi Shankar and the Beatles in the mid-1960s. The sitar is widely used in the Hindustani music of North India — in addition to Carnatic music, the other major classical tradition of India. The sitar and several other North Indian instruments like the tabla reflect a syncretic heritage shaped by centuries of cultural exchange between India, Persia, and Central Asia. Persian culture served as the high culture of North Indian courts for over 600 years, especially under the Mughals, and the very name ‘sitar’ is of Persian origin.

But the Mughal empire never extended deep into South India, where Carnatic music developed within a different cultural milieu. Its instruments remained closely tied to Hindu temples and the courts of empires like Vijayanagara and Thanjavur. Three of the four instruments heard in this album — the veena, venu (bamboo flute), and mridangam — are long-established instruments mentioned in the Natyashastra, an ancient Sanskrit treatise on music and dramaturgy dated between the 2nd century BCE and 2nd century CE.

Veena

Veena

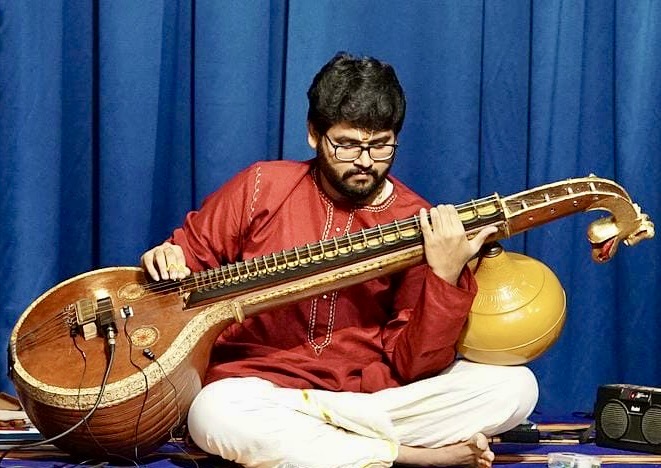

The veena, with its long, fretted neck and gourd-like resonator, has been used in South India for over a millennium. It is one of the most revered instruments in Indian culture: the goddess Saraswati — deity of learning and the arts — is nearly always depicted playing the veena, an act that symbolizes the expression of knowledge and creativity.

The veena brings a striking contrast to the ensemble’s soundscape. Where the violin and flute offer smooth, legato lines that blend easily with one another, the veena’s sound is sharply articulated — each note plucked and distinct. As the lowest-pitched among the Indian solo instruments in this album, it adds depth to the ensemble. Its timbre carries a textured, almost metallic grain, making it both resonant and tactile. It is an instrument that cuts through the blend, anchoring the ensemble.

Venu (Flute)

Venu (Flute)

The venu, a transverse bamboo flute, has a long tradition in Indian music and culture. It evokes the deity Krishna, who is often depicted playing this instrument. To some, it can sound closer to nature than the Western metal flute. In its upper register, the flute takes on a bird-like brightness, while its lower register carries a darker, earthier resonance.

Images of Krishna playing the flute appear in South Indian temple art for at least a millenium, attesting to the instrument’s deep cultural roots. Yet it was only in the 20th century, with innovations introducing the modern eight-hole venu, that the flute assumed its role as a lead instrument in Carnatic concerts.

Violin

Violin

The most common instrument in Carnatic music is the violin — a relatively recent Western import, introduced to South India just over 200 years ago during the British colonial period. Given the ancient Indian lineage of other melodic instruments, it is striking that the violin has become the most widely used. This reflects the instrument’s extraordinary expressivity that echoes the human voice, and its ability to render complex gamakas, the microtonal oscillations and glides so central to Carnatic music.

India has a long history of adapting cultural imports, and the violin is no exception. Several aspects of the instrument have been modified to suit the Carnatic tradition: tuning of the strings, playing posture, and performance technique. A Western violinist could no more play the Carnatic violin than she could play the cello.

Mridangam

Mridangam

The mridangam is the principal percussion instrument of Carnatic music, characterized by its barrel-shaped body and two differently sized drumheads that produce a wide range of tones. An ancient drum depicted in temple carvings as early as the 1st millennium, the mridangam is associated with Lord Shiva and his bull, Nandi — the divine drummer who accompanies Shiva’s cosmic dance, the Tandava.

The mridangam can sound like many instruments at once — pitched and percussive, resonant and dry, lyrical and sharp. With its wide range of tones and articulations, it offers not just rhythm but expression: a deep bass thump, a crisp edge, a singing tone — all emerging from the hands of a single performer. This expressive range gives it an almost melodic presence, allowing it to shape the contour of the music rather than merely mark its pulse. In the album, the mridangam is featured in the final two movements of Field of Dharma.