Diverging Development

Historically, Indian classical music has developed more along the dimension of melody — using dozens of ragas — whereas Western classical music has done so along the dimensions of harmony and counterpoint (and later, timbre), while focusing on a few melodic modes.

Given the deep religious roots of both traditions, part of this divergence may stem from differences in forms of worship. The West’s congregational worship, with its large weekly services, made it feasible to have choirs (initially composed of clergy) singing in multiple registers — encouraging the development of harmony and counterpoint.

Indian worship, in contrast, is often individual in nature, with music focused on personal connection to a deity. This is reflected in a melodic tradition with many ragas, each invoking a particular emotional or spiritual quality.

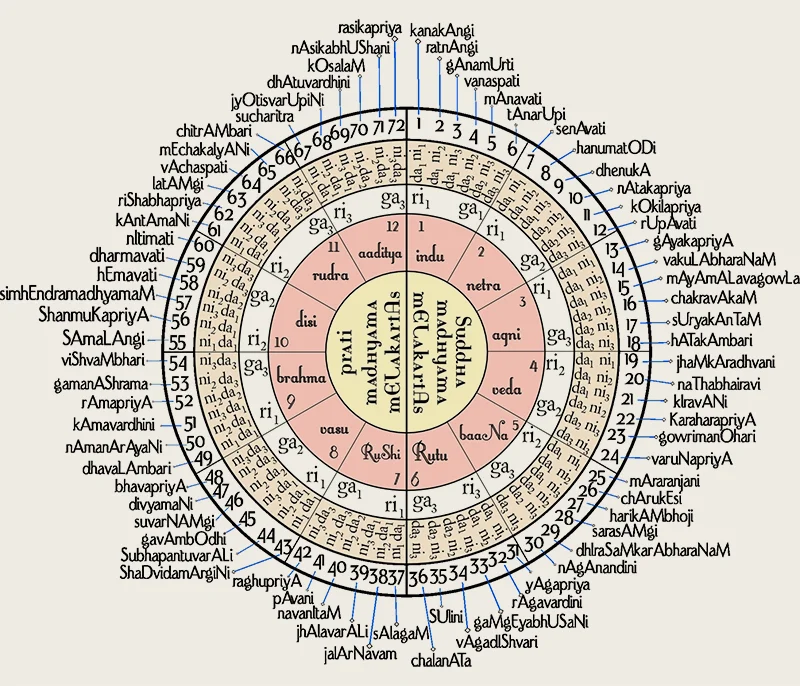

These paths were reinforced by formal systems of codification. In India, theorists like Venkatamakhi (17c.) and Govindacharya (18c.) developed and refined the system of 72 melakarta ragas that underpins melodic development in Carnatic music.

The Melakarta system: a comprehensive organization of the 72 possible parent ragas, based on permutations of the variable scale degrees Ri, Ga, Ma, Dha, and Ni (the tonic note Sa and the dominant note Pa remain fixed).

In the West, the rise of tonal harmony supported the growth of harmonic and contrapuntal writing, with J.J. Fux’s Gradus ad Parnassum (18c.) providing a particularly influential framework for counterpoint pedagogy.

Parallel Evolution

Despite this divergence, there is an interesting parallel in the historical development of the musical forms I use.

The kriti form in Carnatic music — which I draw on in both pieces — began its evolution from the kirtana form in the 15th century, and is widely seen as reaching its peak with the composer Thyagaraja in the 18th century.

Similarly, the fugue emerged from forms like the canzona and ricercar in the 15th century, and reached its height in the work of J.S. Bach in the 18th century. Even the concerto followed a similar arc, beginning in the 16th century.

The establishment of the 72 melakarta raga system in India and the evolution of a modern theoretical framework for counterpoint in the West also took place around the same period, as mentioned earlier.

This parallel development of complex musical forms and systems may reflect a broader aspiration in the early modern era to refine and codify aesthetic structure.

During this time, both South India and the West saw significant musical patronage — from temples and churches, royal courts, and wealthy individuals — which enabled the development and popularization of more intricate musical forms.

Revisiting History

In my work, there’s another connection to the past that I find intriguing.

In Western music, the many medieval church modes (scales) gradually gave way to the major and minor system — in part due to the growing structural demands of counterpoint and harmony.

My project, in a sense, revisits that narrowing of modal variety into major and minor modes. It explores what happens when rigorous counterpoint and its harmonic framework are combined not only with major or minor, but with other modes — and even more so with ragas, with their gamakas and intricate melodic sensibility.

Two stories: Raga & Counterpoint

(Excerpted from the album’s liner notes)

Raga

In a temple courtyard on the banks of the Tungabhadra River, the composer-saint Purandara Dasa sits cross-legged, his voice rising in song. This is 15th-century Vijayanagar, one of the wealthiest cities in the world, and the second largest after Beijing. A crowd gathers around him — at a Hindu temple, Carnatic musicians and dancers transform art into devotion. As worshippers step through the granite temple complex, laying flower garlands at the shrines of Vishnu and Lakshmi, they hear Purandara Dasa’s voice and turn toward the notes echoing across the courtyard.

Each song is an act of prayer directed toward Vitthala, his favorite deity. He sings song after song, each in a different raga or melodic mode that evokes a different mood. One raga conjures serenity and peace. Another, spiritual yearning. In each song, a single melodic line stretches and bends into sinuous shapes, the singular intensity of one voice becoming the musical representation of the individual form of Hindu temple worship. Just as each pilgrim offers their own prayer at each particular deity’s shrine, the Carnatic song makes a musical offering from a lone voice. It is the self-emptying of a single person.

Purandara Dasa’s voice pours beyond the temple walls, across the banks of the river and boulder-strewn Vijayanagar landscape, becoming the tributary from which a tradition would flow.

The kriti form in which Krishnan composes descends from the kirtana, developed by Purandara Dasa. The 15th-century composer is today considered the Pitamaha or forefather of Carnatic music, his musical legacy strengthened by the patronage of 300 years of South Indian wealth, which in his lifetime had been centered around Vijayanagar — a metropolis that the 15th-century Persian ambassador Abdur Razzaq described as “adorned with lofty buildings and delightful gardens, and filled with a population devoted to pleasure and music.”

From Vijayanagar’s music of devotion came a devotion to music — and to understanding its power. Wealthy patrons funded scholars to codify theories of musical structure. Those theories gave rise to a system of 72 seven-note ragas or melodic modes and many more derived ragas. This system provided the theoretical foundation for a profusion of melodic development marking a golden age of Carnatic music, which reached its apex in the kritis of the 18th-century composer Thyagaraja.

This is how one voice learns to unfold itself along supple ascending and descending lines, through forward and backward swerves, bending into patterns whose ever-increasing complexity forms a spiritual testament to an intricately woven world.

Counterpoint

Under the dome of St. Peter’s Basilica in 17th-century Rome, a different kind of complexity rises into the mosaic vaults. An organ interlude by Girolamo Frescobaldi echoes through the cathedral. The singers divide into separate melodic lines that pattern against one another as they move collectively through the Credo, the Sanctus, the Agnus Dei. Each melodic line tells its own musically independent part of the narrative of death and resurrection, yet also contributes to a harmony with its own progressively unfolding story.

This interplay of melodic lines defines counterpoint — a technique which would reach its zenith in Bach’s fugues, as some of the most architecturally complex creations of Western music. Here, too, musical form mirrors the human form of worship, as the multiplicity of the gathered congregation finds its expression in the patterning of multiple melodic lines to make an interwoven whole.

Two traditions, two modes of worship, two musical forms. Although their developments diverged, Krishnan was gripped by the thought that Carnatic and Western classical music belong together. He continually found himself circling around the same questions: What if Carnatic melodic complexity could meet Baroque contrapuntal complexity? What if Purandara Dasa and Frescobaldi had been able to influence each other? And most of all: What would that music sound like?